Forget size, age, awards, geography, even subject matter.

Professors at Harvard Business School have deduced that there are really only four specific types of professional services practices … and that practitioners who commit to the tactics prescribed for their type will be better positioned to succeed.

For law firms, it’s important to understand the four types – and to have the self-awareness to accurately identify their own. From there, niche law firms and discrete practice teams can apply smarter strategies for hiring, marketing and more.

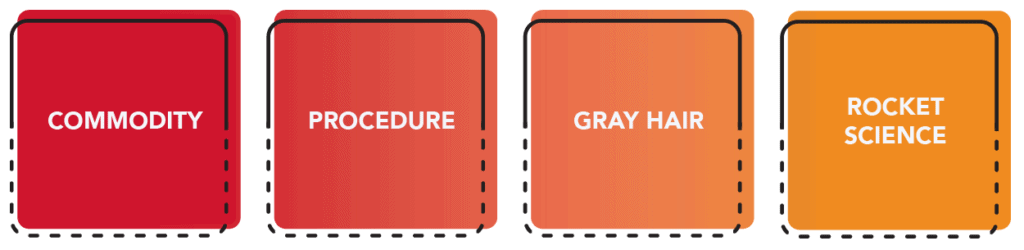

Writing for Harvard Business Review, Ashish Nanda and Das Narayandas shared the four types of practices that comprise the professional services spectrum:

- Commodity

- Procedure

- Gray Hair

- Rocket Science

The Four Types

Let’s look at Harvard’s four types – along with our take on legal industry examples and marketing tactics.

Commodity.

Commodity practices help clients with simple and routine problems by providing “economical, expedient and error-free service,” the authors state. (This type of practice is most vulnerable to threats from legal tech.)

Example: LegalZoom, which offers basic business and family law offerings online at fixed prices

Strategic focus: Efficiency

Profit margin: Single to low double digits

Hiring strategy: A commodity practice will prioritize dependability over creativity or credentials: “They recruit steady individuals who will produce regular output at a reliable pace and quality,” the Harvard professors note. Once on board, new hires will need to deliver standard output efficiently.

How we would market them: Work to demonstrate that you are a safe and easy choice: As a prospective client, I need to know you will solve my problem quickly, with little hassle. LegalZoom’s home page does a great job of touting statistics: 4 million clients served, 550,000 consultations completed, coverage in all 50 states. All with a money-back guarantee.

Procedure.

Procedure practices offer systematic solutions to complicated problems; they may not be novel or sophisticated, but they require careful consideration. (This type of practice is most vulnerable to threats from the Big 4 accounting firms.)

Example: Card Compliant, which applies artificial intelligence solutions for the regulatory, legal and accounting aspects of gift cards

Strategic focus: Established methodology

Profit margin: 20 to 35%

Hiring strategy: Self-aware procedure practices will focus on hiring lawyers with a predisposition to embrace hard work and fight for quantifiable metrics, like billable hours. The Harvard authors relay this sentiment from a procedure practice: “We worry about recruiting professionals who, if asked to work an hour longer on an assignment, convert the conversation into a philosophical debate.” Indeed, once a part of the practice, new lawyers will need to understand and apply the firm’s particular protocols.

How we would market them: Fall back on the adage that it’s easier to sell aspirin than vitamins: Procedure practices frequently exist to handle tedious, complex problems – the proverbial business headache. Card Compliant warns gift card issuers of the myriad landmines they can encounter, from multiple jurisdictions to multiple regulators; it shows the high stakes at play in a large volume of small-dollar transactions.

Gray Hair.

Gray-hair practices are distinguished by their experience in notable cases and transactions – client problems made easier by the application of previous lessons learned (or the swagger of previous battles won).

Example: The litigation boutique Quinn Emanuel

Strategic focus: Platform of victorious professionals

Profit margin: 35 to 50%

Hiring strategy: Individuals with “wisdom gleaned from experience,” the authors describe. In the legal sector, this could include high-profile laterals or junior lawyers with prestigious academic credentials. Because experience is the hallmark of the gray-hair practice, the firm will look for new additions to apply their experiential learnings to future matters.

How we would market them: Be ruthless about collecting, cataloging and sharing examples of experience; use the track record to assure your prospects you have handled a problem like theirs (to sensational results). Upon landing at the Quinn Emanuel website, users see a ticker of recent victories (along with the announcement of a recent award declaring it the “No. 1 Most Feared Law Firm in the World”). Another page is dedicated to notable victories with the casual note that Quinn Emanuel has obtained five nine-figure jury verdicts.

Rocket Science.

As defined by the Harvard team, “a rocket-science practice addresses idiosyncratic, bet-the-company problems that require deep expertise and creative problem-solving.”

Example: Forgive the literal rocket tie-in, but a prime example is Hogan Lovells’ Space and Satellite group

Strategic focus: State-of-the-art expertise

Profit margin: 50% or more

Hiring strategy: “Brilliant, creative professionals.” A rocket-science practice does not solely rely on the charm of its rainmakers; social savoir-faire can be a distant second to a beautiful mind. To maintain the firm’s competitive edge, rocket-science lawyers must stay visible, credible and cutting-edge.

How we would market them: Develop a position as the thought leader in the field, and protect it with constant visibility; speak and write constantly, and make it hard, if not impossible, for any other firms to catch up. Hogan Lovells’ space lawyers speak at industry events, like the MilSat Symposium; the firm also seeks industry-specific awards in addition to the legal stalwarts. Its attorneys have been recognized by Space & Satellite Professionals International and Women in Space, among others.

How Do I Know My Type?

It’s important to note that none of these is “better” than the others: Managed correctly, all four can be very successful.

However, in a profession that often attracts individuals with high ego drive, there can be a tendency to overreach: The Harvard professors share that most practice leaders place themselves in “gray hair” or “rocket science,” despite evidence to the contrary.

You cannot self-select your type: It is determined by what clients need (as defined, perceived and felt by the clients) and what they are willing to pay. Margins are the best indicator.

Why Does This Matter?

When firm management does not accurately assess or understand their position, problems can arise. Consider this hypothetical from Nanda and Narayandas: A leader erroneously inflates a practice into a rocket-science practice. He recruits expensive talent with the lure of exciting, creative work. The clients view their problems as straightforward; they want efficiency and low rates. Both will end up frustrated.

What Do I Do Now?

First, commit. Although it may be tempting to think about your practice like a mutual fund, with a little of each of the types, don’t. As Nanda and Narayandas write: “The best-performing practices have a sharp focus. Clients know what services each practices offer, practice leaders know which performance levers to pull, and recruits know what type of work they’ll do.

“A diffuse profile dilutes a practice’s identity and renders it a jack of all trades and a master of none.”

(I may print this last sentence on t-shirts.)

Second, prepare to play the long game. Over a long enough period of time, the most rocket-science practice can go to gray-hair to procedure to commodity. Cruise through the LegalZoom offerings for examples, from patents to corporate dissolutions. To safeguard a higher-end practice, study the marketplace relentlessly. Invest. Experiment.

Third, get selective. If you are a commodity or procedure practice, stay laser-focused on the solutions you provide profitably – and make them even better. If you are or aspire to be a gray-hair or rocket-science practice, stop offering services seen as commoditized. Get disciplined about which proposals you chase (an RFP checklist can help).

This final point is especially important in the wake of COVID-19 and the uncertainty of 2020, which tempted many law firms to take on incompatible work just for work’s sake. Gray-hair and rocket-science practices must heed the warning of the Harvard professors: “Once a practice has become commoditized in the market’s view, it’s extremely difficult for it to move back toward the premium end of the spectrum, and the long-term damage to the practice can be devastating.”